We’ll start with the basics.

The Chesapeake Bay is a body of water on the East Coast of the United States of America, located roughly midway between Maine and Florida. It’s the largest estuary in the United States and the Third largest in the world. It is bordered by the states of Maryland and Virginia, and if you include the rivers, extends to Washington, D.C. Baltimore, Chestertown. Oxford, Cambridge, Richmond and Norfolk. Its origin to the north by Havre de Gras is the Susquehanna River (with water from Maryland, New York and Pennsylvania) and emerges into the Atlantic Ocean at Norfolk and Virginia Beach.

On the Western shore, the Bay receives freshwater from the Susquehanna, Patapsco, Patuxent, Potomac, York and James Rivers (with water from West Virginia), and from the Eastern Shore, from the Chester, Wye, Miles, Choptank, and Nanticoke Rivers (with water from Delaware). It covers a large area, with around 4,480 square miles of surface area and a shoreline of over 11,000 miles. It ranges from 3.4 miles wide (at Annapolis, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, Kent Island and the Thomas Point Lighthouse) to 35 miles wide (from the mouth of the Potomac River, past Smith Island and across to Crisfield and Saxis on the Eastern Shore). The Bay holds more than 15 trillion gallons of water but with an average depth of only 21 feet.

The Chesapeake Bay has a multitude of ecological environments that supports 348 species of finfish and 173 species of shellfish, many of huge economic importance – locally and globally, including blue crabs, oysters and rockfish. The Port of Baltimore is the nineth largest port in the United States.

The Bigger Picture – Life on the Chesapeake: Where Culture, Commerce, and Conservation Meet

The Chesapeake Bay stretches like a liquid lifeline through the Mid-Atlantic, cradling communities that have drawn sustenance and livelihood from its waters for millennia. Today’s bay residents are the latest chapter in a human story that began with indigenous peoples who recognized the extraordinary bounty of this estuary long before European contact.

A Heritage of Watermen

Dawn breaks over the Eastern Shore as watermen ready their boats, continuing traditions passed through generations. These small business owners—crabbers, oystermen, and fishermen—represent a distinctive Chesapeake culture. Their workday follows rhythms established by ancestors who pulled similar harvests from these same waters.

“My grandfather taught my father, and my father taught me,” says James Wilkins, a third-generation crabber from Crisfield, Maryland. “The bay provides, but you have to respect it. You have to understand its moods and seasons.”

These watermen form the backbone of local economies in waterfront towns like St. Michaels, Onancock, and Tangier Island. Their daily catch supplies local restaurants where visitors can taste the bay’s bounty hours after it’s harvested.

Economic Powerhouse of Ports

While small boats harvest seafood, massive container ships and tankers navigate the deeper channels of the bay. The Port of Baltimore and Port of Norfolk-Virginia Beach represent commercial activity on an entirely different scale, handling billions of dollars in international trade annually. Massive Navy ships navigate the waters of the lower Bay, and sometimes the shipyards of Baltimore for repair. These bustling ports employ thousands in logistics, shipping, and related industries. The Chesapeake’s natural deep harbors have made it a commercial gateway since colonial times, connecting the American interior to global markets. Today’s massive cargo operations stand as modern extensions of the maritime commerce that has defined the region for centuries.

Ancient Traditions Continue

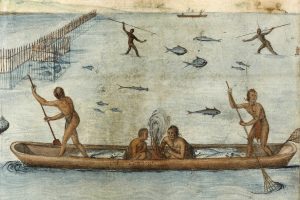

This relationship between people and the bay traces back thousands of years. Native peoples—including the Powhatan, Piscataway, and Nanticoke—harvested oysters, fished the shallows, and traveled its waters in canoes. Archaeological evidence reveals enormous shell middens (discarded oyster shells) testifying to the bay’s historical abundance and its importance to indigenous communities. These first inhabitants established sustainable harvesting practices born from intimate knowledge of the bay’s ecosystems—wisdom that resonates with today’s conservation efforts.

Tourism Transforms Shorelines

The Chesapeake draws millions of visitors annually who come to sail its waters, explore historic towns, and savor its seafood. Tourism has transformed former fishing villages into destination communities where historic waterfronts now feature boutiques and bed-and-breakfasts alongside working docks.

Annapolis, with its colonial architecture and sailing culture, exemplifies this blend of heritage and tourism. Visitors can watch sailboat races in the morning, tour historic sites at midday, and dine on locally-harvested seafood in the evening.

A Vital Ecological Nursery

Beyond human commerce, the Chesapeake serves as one of North America’s most productive estuaries. Its brackish waters provide essential breeding grounds for countless fish species, including striped bass, blue crabs, and oysters. The bay’s marshes and wetlands shelter juvenile fish and crustaceans while offering habitat for hundreds of bird species.

Each spring, migratory birds follow the Atlantic Flyway, stopping to feed in the bay’s rich wetlands. Great blue herons stalk the shallows while osprey dive for fish, all dependent on the estuary’s ecological health.

Balancing Human Needs and Environmental Health

With over 18 million people living in the Chesapeake watershed, human activity inevitably impacts the bay. Runoff from roads carries oil and chemicals. Fertilizers from suburban lawns and agricultural fields trigger algal blooms. Development consumes wetlands that once filtered pollutants naturally.

“Everything flows downhill to the bay,” explains Dr. Sarah Jenkins, an environmental scientist with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. “What happens on land—from farming practices to how we manage stormwater in subdivisions—directly affects water quality.”

Conservation efforts now focus on sustainable development practices, improved wastewater treatment, and restoration of natural filters like wetlands and forest buffers. Initiatives to replant oyster beds leverage these bivalves’ remarkable ability to filter water—a single oyster can clean up to 50 gallons daily.

The Future of the Bay

The Chesapeake Bay exemplifies both the challenges and possibilities of balancing economic vitality with environmental stewardship. Its waters support livelihoods ranging from family crabbing operations to international shipping conglomerates, while simultaneously serving as critical habitat for countless species.

As climate change brings rising sea levels and shifting weather patterns, bay communities face new challenges. Yet the enduring relationship between the people and waters of the Chesapeake suggests a resilience born from thousands of years of adaptation.

The bay has always been more than a geographical feature—it’s the cultural and economic heart of the region. Its future depends on continuing to honor this relationship through thoughtful management of both human activity and natural resources, ensuring that watermen will still cast their crab pots into productive waters for generations to come.