Nautical terms are usually completely functional in origin – abandon ship might be obvious, but what about ‘Port’ and ‘Starboard’? Well, we’ll have to go quite a way back in time for that answer. We have to go back to Viking times…..

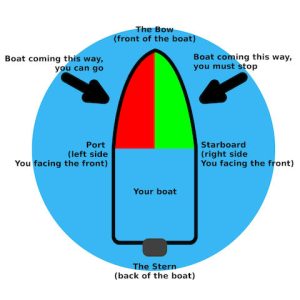

Firstly, the port side of a ship is on the left while the starboard side is on the right. At night, these are designated by lights: red on the port side and green on the stardoard side (remember it by ‘port’ and ‘red’ have fewer letters than ‘starboard’ and ‘green’). On Therapy, the lines that haul up the flags and the lines that pull the boom over to the left and right are color coded.

Role of the Vikings

The Vikings were absolute masters of the seas – they had to be, living in the harsh conditions of Scandinavia where waterways were often the best (or only) way to travel and trade. Their innovative ship designs and seafaring prowess let them explore and influence territories from North America to the Mediterranean, and even into Arctic waters.

Their most famous vessel, the longboat (or longship), was an engineering marvel. These ships were typically 60-80 feet long but only 15-20 feet wide, with a shallow draft that allowed them to navigate both open seas and shallow rivers. The genius of their design was the flexibility – the long, narrow hull could bend and twist with the waves rather than fighting against them. Think of it as more like a sea serpent gliding through the water than a modern rigid boat.

The steering oar (stjórn-borði) was fundamentally different from today’s rudders. Picture a massive oar, about 20 feet long, mounted on the right side near the back of the ship. So, when the ship was brought into a port and secured to the jetty (often made of stone) they would secure to left side of the ship (the ‘Port’) side so the stjórn-borði could not get damaged – hence ‘Port’ side and ‘Starboard’ side.

Unlike a modern rudder that’s fixed vertically in the center of the stern and pivots, this steering oar was angled into the water and could be both rotated and lifted. It worked more like a combination of a rudder and a paddle. The skilled helmsman (called a stýrimaðr) would manage this oar, which required incredible strength and finesse – imagine trying to steer a 70-foot ship with what’s essentially a giant paddle! This steering oar system was actually quite sophisticated for its time. When sailing downwind, the oar could be used to prevent broaching (when the stern gets pushed sideways by waves), and in heavy seas, it could be partially lifted to prevent damage – something you can’t do with a fixed rudder. The Vikings were so good with these steering oars that they could navigate through ice fields and handle the treacherous North Atlantic waves.

The Vikings’ influence on maritime technology and navigation was so profound that many of their innovations persisted for centuries. They were the first to develop reliable methods of open-ocean navigation, and their shipbuilding techniques influenced naval architecture well into the medieval period. The term starboard (from stjórn-borði) represents more than just a nautical direction aboard moder vessels – it’s a linguistic fossil that tells us about how these incredible mariners solved the fundamental challenge of steering large vessels. Every time modern sailors use the word “starboard,” they’re unknowingly paying homage to those Viking helmsmen who steered their longships across uncharted waters with nothing but a well-crafted oar and their own skill.

The Vikings’ influence on maritime technology and navigation was so profound that many of their innovations persisted for centuries. They were the first to develop reliable methods of open-ocean navigation, and their shipbuilding techniques influenced naval architecture well into the medieval period. The term starboard (from stjórn-borði) represents more than just a nautical direction aboard moder vessels – it’s a linguistic fossil that tells us about how these incredible mariners solved the fundamental challenge of steering large vessels. Every time modern sailors use the word “starboard,” they’re unknowingly paying homage to those Viking helmsmen who steered their longships across uncharted waters with nothing but a well-crafted oar and their own skill.